Misconceptions regarding diagnostic criteria

The Oxford Criteria

The Ramsay Definition

The Fukuda Criteria

The Canadian Consensus Criteria

The International Consensus Criteria

The National Academy of Medicine Criteria/IOM Criteria

Criteria Comparisons

Criteria Comparison Chart

Additions and corrections

Introduction:

We know that our community continues to wrestle over the appropriate diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis to the point that it has can cause contention and consternation in our interactions and discussions. Concern around the legitimacy of the several diagnostic criteria in use is a natural outgrowth of the disbelief and stigma around ME.

The purpose of this article is to provide a source of neutral disambiguation to which people with ME, providers, and researchers can refer — to inform rather than convince. Over the course of the article, we can and must address some prominent misconceptions in search of better clarity. However, there are no conclusions drawn here. That is up to the reader.

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”14″]The article proceeds as though these three premises are a given: a criteria that is useful as a diagnostic tool must include an accurate description of symptoms that are either unique on their own, or unique in combination. For purposes of education, a diagnostic criteria is useful if it provides an accurate picture of how the disease might present in clinic. Finally, a criteria is useful for treatment that includes the greatest number of people who suffer from the disease, without including those who do not.[/pullquote]We will discuss the following criteria and disease definitions: Oxford, Ramsay, Fukuda, the Canadian Consensus Criteria (CCC), the International Consensus Criteria (ICC), and the National Academies of Medicine Criteria (IOM or NAM). Inclusion ought not be considered equivalent to recommendation or endorsement.

Because the diagnostic criteria has been such a point of contention, quotes about the disease and criteria have been taken out of context in order to support interlocutors’ favored arguments. To mitigate this issue, each section will link back to the original document, allowing readers to see where the information originated and to explore the context as necessary for clarification.

This is a long article! Please feel free to bookmark and return.

Misconceptions about diagnostic criteria

- ME has no single biomarker that may be used in diagnosis. This is not to say that there are no abnormalities in people with ME. Some of these include decreased natural killer cell function (or number), and other immunological abnormalities; metabolic changes; and white matter hyperintensities on MRI. However, none of these are unique to ME. Shifts in natural killer cell function and metabolic shifts such as we see in ME are also seen after other significant biological trauma, including sepsis, physical trauma, or severe burns. White matter hyperintensities can be seen in several different diseases and disorders, including migraine. While a clinician has tools that will show signs of illness in people with ME, there’s no way to identify someone with the disease through such testing alone.The use of symptom-based criteria doesn’t make ME any less real than the many other complex chronic diseases and disorders for which there is no biomedical test and which must also be diagnosed the same way. That includes hEDS, autism, MCAS, POTS, and many, many others.Without a unique biomarker, there is no way to ‘prove’ a criteria identifies patients with the same illness. However, we can argue a criteria to be more or less useful than others.

- The criteria that captures the fewest patients must be correct. A researcher could create a diagnostic criteria that states that on top of meeting Fukuda, the patient must have one blue eye and one brown. That would create the smallest criteria for ME or CFS in existence, but this would not make it more likely to be an accurate or useful criteria for people with ME. The number of patients captured is unrelated to a diagnostic criteria’s accuracy or usefulness, when divorced from other considerations.

- Not explicitly listing exclusions means diagnosis without checking for other illness. Diagnosis of all disease requires ruling out other, similar conditions, even where biomarkers are present. This is implicit in the diagnostic process.

- If clinicians and researchers we know participated, the criteria is probably good. Clinicians and researchers we know participated in all the criteria currently in use to greater and lesser degrees, with significant overlap in who worked on which criteria. The criteria must stand on its own merits.

- We can apply a diagnostic criteria to previously-investigated populations. Determining whether or not a patient meets all the requirements of a diagnostic criteria is often not possible without a clinical examination. At the very least, targeted questions about intensity, duration, and nature of required symptoms must be elicited. For this reason, it is often not possible to retrospectively determine whether a population examined for one criteria meets others.

- Every diagnostic criteria must serve the same purpose.In medicine, the goal is to provide appropriate interventions as swiftly as possible in order to address symptoms of disease. In research, the goal is to have as well-characterized a population as possible to investigate aspects of the disease-process or determine effective treatments. These differing goals may mean that some criteria are more appropriate for research and some are more appropriate for clinical practice.

- A criteria is useful for diagnosis if the symptoms on their own or in combination are unique enough to separate it from others;

- A criteria is useful for treatment if it includes as many people with the disease as possible while still excluding those who do not;

- A criteria is useful for medical education if its symptoms accurately convey how the disease may present in a clinical setting.

The Oxford Criteria

Misconception:

The Oxford Criteria only requires long-term fatigue.

Clarification:

There are two subsets of the Oxford Criteria; one requires infectious or post-infectious onset.

Misconception:

The Oxford Criteria presents the disease as psychiatric.

Clarification:

Severe psychiatric illness is exclusionary in Oxford. Suggested comparison groups include people with neuromuscular disorders (such as MS or ALS) and other conditions that may cause debility. Oxford also suggests depressive disorder as a comparison group, making it clear that the original conception of the disease was not as a kind of vegetative depression. However, the less stringent version of the Oxford Criteria is frequently and almost exclusively used by biopsychosocial theorists, who often conceptualize the disease as a psychosomatic syndrome.

The Oxford Criteria is often used in biopsychosocial (BPS) research in the UK. It has been included here so that readers can understand the implications of using this diagnostic criteria for studies of people with ME.

Oxford:

The Oxford criteria requires that severe, disabling fatigue of new origin be present. The fatigue must have both cognitive and physical effects and not be due to any other fatiguing disease or disorder, such as anemia. The fatigue must be present for at least six months and must have been present for at least 50% of the time. Like Fukuda, Oxford explicitly excludes severe mental illness such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Myalgias (muscle pain), mood disturbances, and sleep disturbances may be present, but these are not required for diagnosis.

Oxford, post-infectious (Post-Infectious Fatigue Syndrome):

In addition to meeting the Oxford criteria above, the disease must be proved to have initiated during or in the wake of an infection, with confirmation from clinician and/or laboratory of the infectious state. The disease must persist at least six months after the infection has cleared.

Click here to read the Oxford Criteria on pubmed or click on the popout below.

The Ramsay definition

Note: There are a great number of misconceptions floating around about Ramsay’s definition. This may be because the definition is represented in A. Melvin Ramsay’s book Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Postviral Fatigue States, subtitled The saga of Royal Free disease. It is not a published paper, and is not available online in its entirety.

Misconception:

Ramsay’s criteria says…

Clarification:

Ramsay’s book outlines a disease definition rather than a diagnostic criteria. A diagnostic criteria is written such that clinicians can diagnose the disease by determining whether certain symptoms or biomarkers are present. Ramsay’s book outlines a narrative description of disease etiology and presentation without stating which symptoms (or how many) must be present for diagnosis save ‘muscle fatiguability’ of which Ramsay says, “Without it, I would be unwilling to diagnose a patient with ME”; and low-grade fever in the acute stages. Ramsay did not attempt a diagnostic criteria, and his disease definition should not be labeled as one. For the same reason, Ramsay’s definition is not suitable as an inclusion criteria for research. Despite that it is not a diagnostic criteria, it remains a valuable tool for clinicians.

Misconception:

Ramsay’s definition specifies that only Virus X causes ME.

Clarification:

Ramsay references more than one type of infection that may precede ME onset in his accounts of historical epidemics, including poliomyelitis and Coxsackie B. Ramsay also states “…it [ME] may be sudden and without apparent cause, as in cases where the first intimation of illness is an alarming attack of acute vertigo, but usually there is a history of infection of the upper respiratory tract or, occasionally, the gastrointestinal tract with nausea and/or vomiting.” Ramsay says, then, that infection “usually” precedes onset, but sometimes there is no apparent infection; and that when there is not, it is often heralded instead by what appears to be autonomic symptoms. Ramsay acknowledges some cases of ME do not appear to be post-infectious.

Misconception:

Ramsay’s definition describes acute onset only.

Clarification:

Ramsay describes both acute and ‘insidious’ cases when he describes the history of the disease, stating, “…the onset of the disease was acute in four cases, and insidious in fifteen” in regards to one outbreak (pp. 16, New York outbreak, 1950). In a medical context, refers to a more gradual onset.

Myalgic encephalomyelitis and postviral fatigue states has one of the most complete accounts of the history and presentation of the disease — in part because it is a book rather than a research paper or consensus criteria (see ‘misconceptions’). The book details symptoms not described elsewhere; and in part because it is the only definition or diagnostic criteria to distinguish the symptoms of early onset from the symptoms of the chronic disease.

Acute symptoms/peri-onset symptoms (pp. 29)

According to Ramsay, peri-onset symptoms include persistent and profound fatigue and a “medley” of potential other symptoms, such as headache; giddiness; muscle pain, cramps, or twitching; muscle tenderness or weakness; parasthesia (unusual sensations, typically in extremities); frequent urination and difficulty with fluid balance; and sensory disturbances such as tinnitus, deafness alternating with hyperacusis, or blurred vision; and malaise, a general feeling of being ill or unwell. Ramsay also points out that hypoglycemia is common around onset, and mentions that in some cases it is extreme enough to warrant hospitalization. Finally, he states that “all cases” will run a low-grade fever seldom exceeding 100F (28C).

Ramsay also mentions swollen lymph nodes and post-exertional malaise (though he doesn’t label it as such) in his description of peri-onset symptoms, stating, “if muscle power is found to be satisfactory [in minor/moderate-presenting patients], a re-examination should be made after exercise”.

Symptoms of the chronic condition (pp. 29)

Ramsay divides symptoms of the chronic condition into three main categories: issues with the muscular, circulatory, and central and autonomic nervous systems.

Muscular system (pp 30)

Muscle fatigability, in which it may take days for normal function to return, must be present in all cases, although minor or moderate cases may only show this post-exertionally. In severe cases, muscular spasm/twitching is “a prominent feature”, along with swollen bands in the muscle. In less severe cases, tender points in the trapezius (neck and upper back) or gastrocnemius (back of the lower leg) muscles may be found. Ramsay also mentions issues with fine motor control.

Circulatory system (pp 30)

Ramsay mentions cold extremities and hypersensitivity to cold, along with an ashen-grey pallor preceding worsened symptoms.

Central and autonomic nervous system (pp 31)

Problems with memory and concentration are central, along with emotional lability (mood swings, sometimes dramatic; Ramsay gives “bouts of weeping” as an example).

Ramsay goes on to detail a number of issues with cognition, including difficulty with reading comprehension, choosing the wrong word when speaking (paraphasia, dysphasia), difficulty with word-finding (anomia, anomic dysphagia), alterations in sleep rhythm and/or vivid dreams.

Finally, Ramsay mentions symptoms with likely autonomic origins, such as sensory sensitivity, increased frequency of urination, episodic sweating, and orthostatic tachycardia (POTS).

Onset and recovery

Onset is described as being post-infectious, typically in the upper respiratory tract or digestive tract, but with some cases arising in the absence of clear signs of infection; Ramsay states that the first troubling symptom in these cases is often “an alarming attack of vertigo” (see ‘misconceptions’).

Ramsay states that “most cases” make a complete recovery and that only 25% of people with ME will have the disease ten years or longer. However, the numbers Ramsay uses arise from polls of local support groups, and it is unclear how they tracked recovery.

Ramsay suggests absolute rest in the early stages of the disease, and that relapses can be caused by “excessive physical or mental stress, or both”, or new infection (pp 32). Ramsay speaks of relative remissions lasting years before the disease relapses, and calls this one form of the disease. The other he identifies as a form in which “no remission occurs”. Ramsay paints this form of the disease as more severe.

Click on the popout below to read the chapter regarding diagnostic criteria in Ramsay’s Myalgic encephalomyelitis and post-viral fatigue states.

The Fukuda Criteria

Misconception:

The Fukuda criteria does not list post-exertional malaise as a symptom.

Clarification::

The Fukuda criteria includes but does not require post-exertional malaise. It is one of eight symptoms of which four are required for diagnosis. That means a patient may be diagnosed using Fukuda even if they don’t experience PEM. However, PEM would count as evidence for diagnosis of CFS.

The Fukuda Criteria fatigue that is “unexplained, persistent or relapsing”, “of new or definite onset, [and] is not the result of ongoing exertion; is not substantially alleviated by rest; and results in substantial reduction in previous levels of occupational, educational, social, or personal activities.”

In addition to this fatigue, at least four of the following eight symptoms must be present (or relapsing-remitting) for at least six months. These other symptoms cannot have preceded the onset of the fatigue described above, and include: substantial impairment in short-term memory or concentration; sore throat; tender lymph nodes; muscle pain; multi-joint pain without swelling or redness; headaches of a new type, pattern, or severity; unrefreshing sleep; and post-exertional malaise lasting more than 24 hours. Click on the pop-out below to check out the Fukuda criteria.

Click here to see The Fukuda Criteria.

A criteria that requires a certain number of symptoms out of a list of potential symptoms is called a polythetic criteria. All the criteria discussed here have polythetic elements, save the two Oxford criteria. Polythetic criteria can mean that people with varying symptoms may have the same diagnosis. For example, there are 163 different possible combinations of symptoms that would still qualify to meet Fukuda criteria. If we consider issues with short-term memory and issues with concentration two potential items rather than one, this number of combinations increases.

Fukuda has an extensive list of exclusionary conditions, including drug and alcohol abuse, depression with psychotic features, side effects of medication, and eating disorders. Fukuda also lists severe obesity as exclusionary (BMI > 45).

The Canadian Consensus Criteria

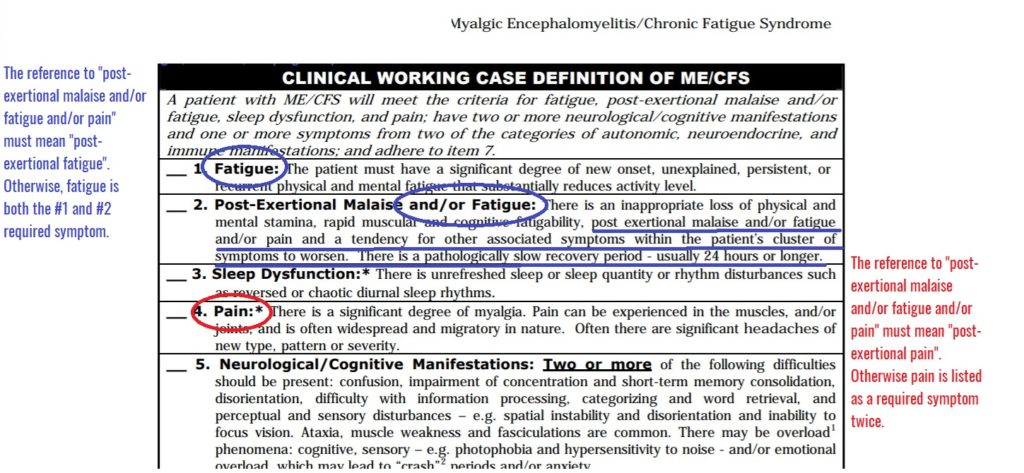

Misconception: CCC doesn’t really require PEM.

Clarification: The Canadian Consensus Criteria refers to “Post-Exertional Malaise and/or Fatigue”. Grammatically, this may be taken as “post-exertional malaise (symptom 1) or fatigue (symptom 2)”; or “post-exertional malaise and/or post-exertional fatigue”. The latter is the only possible interpretation for two reasons.

First and most obviously, the first symptom required for CCC diagnosis is fatigue on its own. Why would that also be the second required symptom? That is not a sensible interpretation.

Second, the paragraph directly below the heading further explores the symptom. The text describes the second required symptom as “post exertional malaise and/or fatigue and/or pain and a tendency for other associated symptoms within the patient’s cluster of symptoms to worsen. There is a pathologically slow recovery period – usually 24 hours or longer” making it clear that each of these symptoms is worse post-exertionally with slowed recovery (from exertion) rather than meant to be considered separate from exertion.

Finally, if any doubt remains, pain is also listed as its own, separate required symptom. If #2 did not mean “post-exertional pain” then pain is another symptom that would be required twice over.

Click here to see an image with the description in a new window, or click on the image below.

The Canadian Consensus Criteria was written by an international panel, despite the name.

Required symptoms:

The criteria requires that four symptoms be present:

The first is fatigue of new onset, unexplained by other conditions, either persistent or recurring, with physical and mental dimensions, that substantially reduces activity level.

The second required symptom is post-exertional malaise and/or post-exertional fatigue, and/or post-exertional pain, described as “…an inappropriate loss of physical and mental stamina, rapid muscular and cognitive fatigability, post exertional malaise and/or fatigue and/or pain and a tendency for other associated symptoms within the patient’s cluster of symptoms to worsen. There is a pathologically slow recovery period – usually 24 hours or longer.” (See misconceptions for issues with this point.)

The third required symptom is sleep issues. The Canadian Consensus Criteria states that “There is unrefreshed sleep or sleep quantity or rhythm disturbances such as reversed or chaotic diurnal sleep rhythms.” We can summarize this symptom by stating that the patient must have unrefreshing sleep; insomnia and/or hypersomnia; and/or an inverted sleep cycle.

The fourth required symptom is pain; the CCC points out that this includes headaches of a new type, pattern or severity; muscle pain; and/or joint pain. They also emphasize that the pain may be bothersome in different places at different times (“migratory in nature”).

The CCC requires that the symptoms be present for at least 6 months in adults and at least 3 months in children. Like Ramsay, it acknowledges that there is gradual onset in some, while most experience acute/sudden onset of symptoms.

Polythetic symptoms:

Beyond these four required symptoms, CCC further requires at least two neurological or cognitive symptoms; and at least one symptom from two of the following three categories: autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immune.

Potential neurological symptoms (of which the patient must have at least two) include: trouble concentrating; confusion; disorientation; difficulty with information processing, categorizing and word retrieval; perceptual and sensory disturbances, such as spatial instability, disorientation, and inability to focus vision; ataxia, muscle weakness, and fasciculations; and sensory sensitivities such as photophobia, hyperacusis (sound sensitivity), potentially leaning to emotional overload and/or anxiety. There are some places here where it is unclear whether a line contains one potential symptom or counts as more — ataxia, muscle weakness, and fasciculations, for example, appear to go together as one consideration but may constitute three.

The patient must have at least one symptom from at least two of the following categories: (1) autonomic: orthostatic intolerance; light-headedness; extreme pallor; nausea and irritable bowel syndrome; urinary frequency and bladder dysfunction; palpitations with or without cardiac arrhythmias; exertional dyspnea (shortness of breath). (2) neuroendocrine: loss of thermostatic stability; intolerance of extremes of heat and cold; marked weight change; loss of adaptability and worsening of symptoms with stress (3) immune: tender lymph nodes, recurrent sore throat, recurrent flulike symptoms, general malaise, and/or new sensitivities to food, medications and/or chemicals.

Given the sheer number of listed symptoms, it might seem like the number of permutations of patient presentation increases. It does! However, it’s important to keep in mind that all people who meet CCC must have had four symptoms for six months: fatigue; post-exertional issues; sleep disturbances; and pain. This means we are already working with a more specific population by the time polythetic criteria questions come into play. Finally, CCC mentions “overload phenomena”, which is not a standard medical term so far as we can determine, and requires more explanation than given.

See the overview of the Canadian Consensus Criteria document by clicking here.

International Consensus Criteria

The International Consensus Criteria (ICC) is the successor to the CCC with a good deal of overlap in the working groups that produced them.

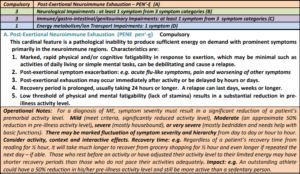

Required symptom:

It has one, required symptom: post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion, defined as the inability to “produce sufficient energy on demand”, with symptoms “primarily in the neuroimmune regions”, and points out that the response may be immediately after activity or delayed. This includes physical and/or cognitive fatigability in response to what may be minimal activity with post-exertional exacerbation of symptoms that may take days, weeks, or longer from which to recover. As a result, there is a substantial reduction in pre-illness activity levels. Due to PENE, symptom presentation may vary a great deal in the same patient over time. Finally, damage from PENE may be cumulative and resting before activity may reduce PENE (see PENE description in the pop-out below or click here)

Polythetic symptoms:

Neurological

ICC requires at least one symptom in at least three categories of four. The four categories are neurocognitive; pain; sleep disturbances; and neurosensory.

Neurocognitive complaints include: difficulty with information-processing, including slowed thought, or impaired concentration — for example, confusion, disorientation, cognitive overload, difficulty with decision-making, slowed speech, and acquired or exertional dyslexia. Short-term memory loss, e.g. difficulty with word-retrieval, difficulty remembering what one wanted to say, or what one was saying; difficulty recalling information or poor working memory are also within the neurocognitive category.

The pain category includes headaches, often involving aching behind the eyes or back of the head, associated with cervical muscle tension; migraine; or tension headaches. It also includes muscular, tendon, or joint pain, as well as pain in the chest or abdomen. It is non-inflammatory and often migratory in nature. Patients may meet fibromyalgia criteria (myofascial) and may radiate.

The sleep disturbance category includes disturbed sleep patterns such as insomnia, hypersomnia, inverted sleep cycle, frequent awakenings, awakening much earlier than before onset, and vivid dreams and nightmares. The patient may also experience unrefreshing sleep (awakening feeling exhausted), and daytime sleepiness.

The neurosensory, perceptual and motor disturbances category includes the inability to focus vision, sensory sensitivities, and impaired depth perception; muscle weakness, twitching, poor coordination, feeling unsteady on one’s feet, and ataxia.

As with CCC, it is sometimes challenging to determine which descriptive terms represent one required symptom and which represent several. For example, certainly poor coordination and feeling unsteady are very similar symptoms and cluster around descriptively similar symptoms (ataxia). This is less concerning here, however, since ICC only requires that the patient have one symptom in any given category.

The criteria notes that neurological symptoms may become more pronounced with fatigue, and adds that abnormal pupillary responses are sometimes seen, though these are not part of the diagnostic algorithm. Like CCC, ICC mentions “overload phenomena” — this needs more description than is included in either criteria.

ICC requires at least three of the following five symptoms or symptom-categories be present: flu-like symptoms that are recurrent or chronic and activate or worsen with exertion, such as sore throat, sinusitis, and tender or enlarged lymph nodes; susceptibility to viral infections with prolonged recovery periods; GI symptoms such as nausea, abdominal pain, bloating, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); genitourinary symptoms such as urinary urgency or frequency or needing to get up at night to urinate; and sensitivities to food, medications, odors or chemicals.

In addition, ICC requires one of the following be present: (1) cardiovascular symptoms such as orthostatic intolerance, which may be delayed; palpitations with/without arrhythmias, or dizziness; (2) respiratory symptoms such as air hunger, labored breathing, or fatigue of chest wall muscles; (3) loss of thermostatic ability (lower than normal body temperature, marked differences in nighttime vs daytime temperatures; sweating episodes; recurrent feelings of feverishness with or without low-grade fever; or cold extremities; and (4) intolerance of extremes of temperature.

A separate category for pediatric ME is included, which states that, “in addition to post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion”, childhood symptoms “tend to be neurological”, including headaches, cognitive impairments, and sleep disturbances. “Migraine may be accompanied by a rapid drop in temperature, shaking, vomiting, diarrhoea and severe weakness. Difficulty focusing eyes and reading are common. Children may become dyslexic, which may only be evident when fatigued. Slow processing of information makes it difficult to follow auditory instructions or take notes. All cognitive impairments worsen with physical or mental exertion. Young people will not be able to maintain a full school program. Pain may seem erratic and migrate quickly. Joint hypermobility is common.”

See the International Consensus Criteria in its entirety by clicking here.

National Academy of Medicine (Institute of Medicine) criteria

The NAM or IOM criteria was conceptualized as a way of enabling general practitioners in the US to more swiftly identify people with ME to refer to specialist care. The IOM report stated that the 2015 criteria was “streamlined for practical use in the clinical setting.”

The NAM criteria, or IOM criteria requires the following three symptoms: fatigue that is persistent and profound, of new and definite onset, that is not the result of ongoing exertion and not alleviated by rest that impairs the ability to engage in pre-illness activity; post-exertional malaise, an “exacerbation of some or all of an individual’s ME/CFS symptoms after physical or cognitive exertion, or orthostatic stress that leads to a reduction in functional ability”; and unrefreshing sleep.

In addition to these required symptoms, people diagnosed with the NAM criteria must present with either cognitive impairment or orthostatic intolerance.

All of the patient’s symptoms must experience these symptoms at least half the time and the intensity of the symptom must be substantial —moderate or severe — and last six months or more. See a pop-out here, and turn to page 210.

NAM adds, “clinical features that may be seen in patients with this disorder are a history of certain infections known to act as triggers for ME/CFS that preceded the onset of symptoms and many types of pain, including headaches, arthralgia, and myalgia. Other complaints, such as gastrointestinal and genitourinary problems, sore throat, tender axillary/cervical lymph nodes, and sensitivity to external stimuli, are reported less frequently (Buchwald and Garrity, 1994; Jason et al., 2013; McGregor et al., 1996). These features, when present, can support the diagnosis of ME/CFS.” However, these are not required for diagnosis.

Criteria comparisons:

This is a lot! Let’s talk about some similarities and differences in the criteria. Remember:

Let’s discuss a few important ways in which the criteria differ.

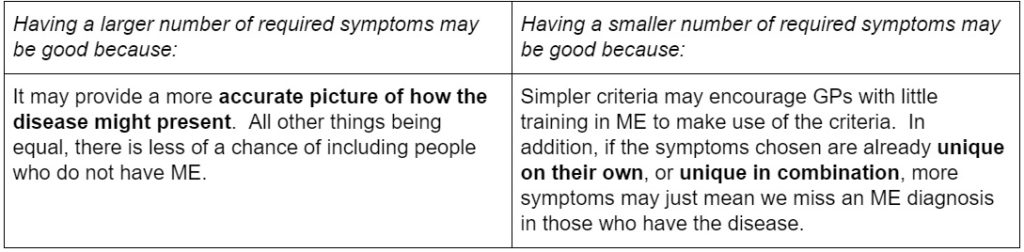

1. Number of required symptoms

Oxford requires the fewest symptoms: just one. CCC and ICC are tied for the greatest number of required symptoms: eight. However, in CCC four of those are required symptoms and four are polythetic. In ICC one of those symptoms is required, and seven are polythetic.

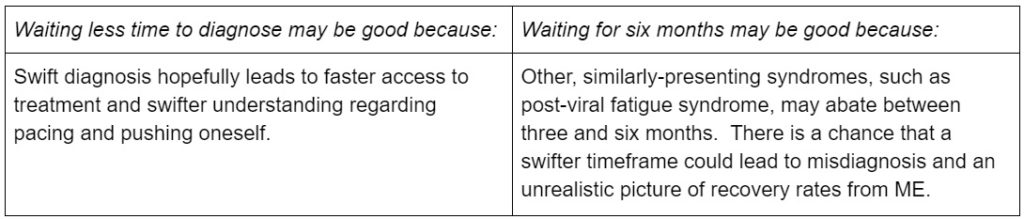

2. Time to diagnosis

Most of the diagnostic criteria that mention a timeframe require six months of symptoms before diagnosis (Oxford, Fukuda, CCC, and NAM). ICC is the exception to the rule, as it may be diagnosed immediately. CCC suggests 3 months for pediatric ME.

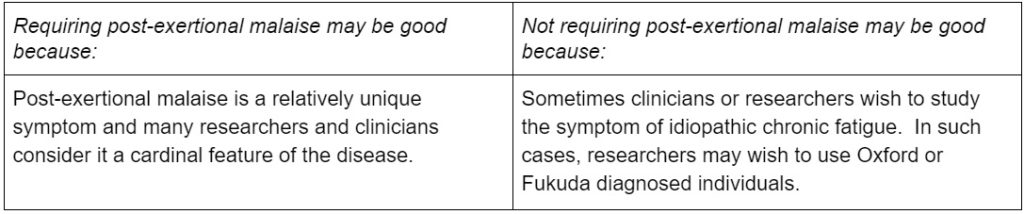

3. Requiring post-exertional malaise

Many of the diagnostic criteria require PEM or an equivalent, but some do not. The diagnostic criteria that require it include the Canadian Consensus Criteria, the International Consensus Criteria, and the National Academy of Medicine Criteria. Arguably, the Ramsay definition requires PEM, given that its definition of muscle fatigability discusses worsened weakness post-exertionally with extended recovery periods. Oxford does not include post-exertional malaise, and Fukuda does not require it.

There is some anecdotal evidence that some people with other complex chronic illnesses experience post-exertional malaise. Though they may not use the term, narrative descriptions make it clear that the symptom is best identified as PEM. While it may be easy to say that they have then been misdiagnosed and ‘actually’ have ME, without a biomarker it should become clear on a moment’s reflection the circularity of this argument.

Criteria comparison chart

Click the pop-out below to see a comparison chart between all of the diagnostic criteria for ME, CFS, or ME/CFS.

When we undertake these important decisions as a community, the most important thing is that we be informed about our choices.

#MEAction launched its six-month Values & Policy Initiative at the beginning of October to bring the community together to discuss our core values, tactics and positions so that we are more unified in our work as a large, diverse community. This initiative will ultimately culminate in a statement of principles and values as well as a formal policy platform, which the community will ratify with an up-or-down vote.

Visit our Values & Policy Initiative webpage to read the editorials we have published around these topics, and see the timeline for upcoming conversations!

56 thoughts on “Demystifying the Diagnostic Criteria for ME and Related disease”

This story claims there are no biomarkers for ME.

“ME has no single biomarker that may be used in diagnosis.”

The truth is that Myalgic Encephalomyelitis has a biomarker. It’s called Encephalomyelitis which is brain/spine inflammation and SPECT or QEEG Scans are used to find it. No Encephalomyelitis- no ME.

Wendy, it’s my personal impression you’re probably right. But without any studies on that, no one will incorporate such a test into a diagnostic criteria. No one has, as of yet.

The ICC -2011 suggests that Neuroimaging should be used.

“ Neuroimaging studies report irreversible punctuate lesions , an approximate 10% reduction in grey matter volume, hypoperfusion and brain stem hypometabolism. Elevated levels of lateral ventricular lactate are consistent with decreased cortical blood flow, mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Research suggests that dysregulation of the CNS and autonomic nervous system alters the processing of pain and sensory input. Patients’ perception that simple mental tasks require substantial effort is supported by BRAIN SCAN STUDIES that indicate greater source activity and more regions of the brain are utilized when processing auditory and spatial cognitive information. Poor attentional capacity and working memory are prominent disabling symptoms.” https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x

Wendy, absolutely true. CCC has a near-identical section re: white matter hyperintensities, and Ramsay has a few really good nuggets of information about the disease you just don’t find anywhere else. IOM had a huge report where they discussed a great number of findings but this article is about requirements for diagnosis.

Jaime

The CCC-2003 is for ME/CFS and it’s inadequate for those with ME. The ICC was specifically written for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis which is not the same thing as ME/CFS. Your financial sponsors might not believe that they are but I can guarantee that anyone with ME-Ramsay, ME-Hyde or ME-ICC live with something much different from the CCC, Fukuda, SEID, Oxford, IACFSME +++ describe. The SEID panel said there was insufficient proof of brain/spine inflammation so you are wrong to suggest that SEID covers #PWME.

You are suggesting Encephalomyelitis is covered by SEID when in fact, SEID was written specifically to replace the anomaly of ME/CFS or CFS/ME. It wasn’t written to replace ME and the CDC took it a step further on Oct 2nd, 2015 by adding Myalgic Encephalomyelitis to the American ICD CM and coded it as G93.3 to match the WHO ICD. It is not the same thing as ME/CFS/SEID and doctors were cautioned to rule out Myalgic Encephalomyelitis before referring to CFS/SEID.

Using the wrong criteria to increase prevalence & funding rather than helping the patient is a prime root of malpractice. “Medical malpractice occurs when a hospital, doctor or other health care professional, through a negligent act or omission, causes an injury to a patient. The negligence might be the result of errors in diagnosis, treatment, aftercare or health management.”

The use of inadequate criteria for a complex neurological disease caused by a virus, is an ‘error in diagnosis’ because it can not help anyone with ME. The ICC can and it was designed to do so by experts.

“ 13 countries and a wide range of specialties were represented. Collectively, members have approximately 400 years of both clinical and teaching experience, authored hundreds of peer‐reviewed publications, diagnosed or treated approximately 50,000 patients with ME, and several members coauthored previous criteria. The expertise and experience of the panel members as well as PubMed and other medical sources were utilized in a progression of suggestions/drafts/reviews/revisions.”

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x

Hi Wendy,

As per my comments below/above, the ICC criteria makes it quite clear that they use the term ME as a synonym for CFS. To quote the first paragraph of the ICC definition:

“Myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), also referred to in the literature as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), is a complex disease involving profound dysregulation of the central nervous system (CNS) [1-3] and immune system [4-8], dysfunction of cellular energy metabolism and ion transport [9-11] and cardiovascular abnormalities [12-14]. The underlying pathophysiology produces measurable abnormalities in physical and cognitive function and provides a basis for understanding the symptomatology. Thus, the development of International Consensus Criteria that incorporate current knowledge should advance the understanding of ME by health practitioners and benefit both the physician and patient in the clinical setting as well as clinical researchers.”

(From: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x)

Carruthers et al do go on in the International Consensus Primer to talk of the need to make clearer distinctions:

“Misperceptions have arisen because the name ‘CFS’ and its hybrids ME/CFS, CFS/ME and

CFS/CF have been used for widely diverse conditions. Patient sets can include those who are seriously ill with ME, many bedridden and unable to care for themselves, to those who have general fatigue or, under the Reeves criteria, patients are not required to have any physical symptoms.”

But this does not assert that ME/CFS is a different illness to CFS/ME, or CFS/CF, or CFIDS (that one clearly didn’t stick) and so on, but rather make the point that diagnoses had been too broad. What the ICP or ICC is saying is that people have been diagnosed in too haphazard a way whatever the term (and this can be applied to ME as well – I’m aware of people diagnosed with “CFS” who are match the ICC criterion much better than some who have been diagnosed with “ME”), and that something needs to be done to improve diagnosis.

As best I can tell, it is quite clear that the ICC is an evolution of the CCC, and both were made, at the time they were made, to diagnose the same illness, rather than to define different things (so the ICC is the ‘best latest’ version of the attempt to diagnose ME/”ME/CFS”/CFS). In doing so, because of the haphazard nature of diagnosis of ME/”ME/CFS”/CFS and related illnesses, it would clearly not cover some people previously diagnosed with ME, ME/CFS or CFS.

Don’t get me wrong – I don’t disagree for a second that some of the other definitions (particularly Oxford and Fukuda) are far too broad, but at this stage it’s not clear, at all, that ME/CFS is different to ME (or, indeed, different to at least a large body of the CFS population). There are many, many positions, but the tests haven’t been established or carried out on the patient populations to know one way or the other. Thus, asserting that Criteria X represents illness Y, at this stage, is inconsistent with clinical or research use (which is all over the place, even within individual countries, let alone when international comparisons are made) or the facts as they stand (which are still yet to be clarified to a point that diagnostic criterion can be assigned to particular groups of patient ‘labels’ with any certainty).

While I think that a discussion of these issues is worthwhile, making claims of things that are neither proven nor in widespread use, as were originally made in this article, is not a great way to demystify anything.

In all these conversations a clarification about which ME/CFS is being referred to is vital for clarity.

ME/CFS prior to 2015 referred to the Canadian consensus criteria.

The ICC was written in 2011.

After 2015, in the US, ME/CFS began to be the label for the description used by the IOM/NAM report. That label then went worldwide.

If we are going to demystify we need to be clear about which ME/CFS we are referring to.

I suggest ME/CFS-SEID for anything that refers back to the IOM report.

I agree it’s important that the criterion are appropriately labelled, but I also think it’s very important to acknowledge that the changing terms over time do not necessarily represent different illnesses (it’s quite clear they weren’t in many of the criteria by the authors) – but rather a better understanding of the nature of the illness (initially understood as ME, CFS or CFIDS, depending on which country you come from, and then an almost-seemingly random mash-up of letters, slashes and dashes since).

ME/CFS was in other places outside the US prior to 2015, for example (it was widely used in Australia before then, that’s for sure), while ME has been used very a very long time in the UK. This doesn’t mean that the ‘main illness of concern’, labelled as ME in the UK, is different to the ‘main illness of concern’ labelled as ME/CFS in Australia. Ie, there’s a core, serious illness that involves constant capacity reduction, PEM and the other bits-and-bobs, and is very strongly suspected to be driven by neuroinflammation (we know neuroinflammation is involved, but as best I understand it we don’t know if this is a cause or a symptom at this stage – although if that’s been progressed I’d love to know – as far as I’m aware, we don’t even know whether it’s one illness or not yet, or rather a group of illnesses with some core similarities). We also know that due to lack of training, neglect and outright prejudice the diagnosis of people suspected to have this illness has been done terribly, pretty much everywhere, such that whichever label is used, there are a group of people that almost definitely don’t have the core illness/illnesses of concern.

What I’ve seen from some sectors of the community, though, is trying to repurpose the language such that one label (usually ME) is used to define the ‘core illness(es) of concern’, and then another label (usually CFS) is used exclusively to describe the people that have been diagnosed with the illness poorly (or were diagnosed such a long time ago, it was with the Oxford/Fukuda criteria (or that other one that’s not much chop), which were too vague to be of much use for anything. Further, the criteria were never developed to diagnose a ‘different’ illness – as best I understand it, it was always with an eye to diagnosing the ‘core illness(es) of concern’, they just attempted to use different labels because of the way CFS comes across.

Thus, that paragraph labelling the different illnesses (far too categorically to reflect actual clinical or research practice, or even ME, ME/CFS and CFS community understanding) creates the illusion of a bunch of ‘core illness(es) of concern’, when really they’re all attempts (even arguably, the Oxford criteria) to get a good diagnostic map of the same illness, whatever label it has. Ie, that paragraph treated the criteria outside of their historical context, and was thus confusing and obfuscating, rather than helping demystify anything – ie, anyone reading that paragraph, and treating it semantically ‘straight-down-the-line’, would think there’s a bunch of different illnesses, that have been _horrendously_ confusingly named, when in fact they’re (at least almost) all having a crack at the core illness, but every new criteria has a crack at a new name, for publicity and/or putting the CFS label to be reasons).

I would like to have seen specific immune tests included.

Also as it was declared a brain dysfunction illness in 1999 at the ME Belgium conference and WHO listed it as a neurogical illness in 1969, further expansion on this aspect is warranted.

I do wish we had enough information on this in ME — to make them part of any diagnostic criteria — but not yet.

I found the chart very useful. Diagnosed in 1996 aged 46 then having to leave work aged 48, when my health improved enough I have been involved with the local ME Group. This really explains the different criteria – and why some are not fit for purpose!

Thank you, Maralyn! I hope the article provided additional context, but I’m aware the article itself is a bit of a doorstop!

MEAction is doing sterling work – more power to your elbows.

However, please note that the word ‘criteria’ is the plural of ‘criterion’; it is incorrect to write ‘..the criteria is…’ – ‘a criterion is…’ – ‘ those criteria are…’

Yessss, John you are correct. I struggled there because people say all the time “the Canadian Consensus Criteria” — they don’t call it the Canadian Consensus Criterion even though it is one, single criterion. So it seems that, grammatically, we call it a (single) diagnostic criteria. One item would be a criterion? If you can shed light on this I’m happy to fix.

This is a huge article – congratulations on putting something so complex together and pulling out the crux of the various diagnostic criterion – this is a significant and useful achievement :).

That said, I’m not sure it demystified the issue, (at least for me, noting that it’s a huge article, and by the time I was half-way through, I’d forgotten the first bit – and writing this feedback is all sorts of painful due to cognitive limitations).

In particular, in the sentence “If and when we refer to disease names, we will refer to Oxford as describing idiopathic chronic fatigue; Ramsay as ME; Fukuda as CFS; CCC as ME/CFS; ICC as ME; and NAM/IOM as ME/CFS (though SEID was suggested, it was not adopted)” has this been done arbitrarily, or there is there a method to it? I know Fukuda’s was an early criterion for CFS, but there’s no doubt that both the CCC, Oxford, and ICC definitions have been used by practitioners for what they have called CFS, while in Britain the Oxford Criterion has been used (however inappropriately) to diagnose ME.

Further, given the ICC definition makes it quite clear that they are using the term “ME” in preference for “CFS” for the same condition in its introductory text, it seems confusing to claim that the CCC and ICC definitions are targeted at different illnesses (as the different term was an exercise in trying to change the term used for a thing, not change the thing that was being diagnosed by the criteria).

Thus, having read all this, while it’s a good walk-through of the various diagnostic criterion, it makes no case at all for the various attribution of names and thus for what the ‘best diagnostic criterion for ME’ (or ME/CFS, or CFS – be they the same or different illnesses), and the judgements it does make early on to differentiate between conditions seem likely to cause widespread confusion amongst the patient community (and readers of this article). Ie, if one person is diagnosed with the CCC, and someone by the ICC, and someone by Fukuda, they could all think they have different conditions when there’s no small chance they could have the same illness. This is above and beyond the somewhat ridiculous ‘culture wars’ that go on with the people trying to define the use of the terms ME, ME/CFS and CFS in a way that would make the Academie Francaise proud, but seems counter-productive in an English-language discussion where common use determines meaning.

It’s especially confusing in the context of the statement “The purpose of this article is to provide a source of neutral disambiguation to which people with ME, providers, and researchers can refer — to inform rather than convince.” Taken semantically, the article makes very specific statements about the most appropriate diagnostic criteria for somewhat arbitrarily determined illnesses. Was this the intent of the article? Is ME Action suggesting it only represents people with ME and not ME/CFS and CFS (so does ME Action only represent people that meet that Ramsay and ICC definitions, but none of the others?*)

I’d suggest replacing the paragraph that reads:

“Generally speaking, when referring to the disease, #MEAction uses ME; however, these diagnostic criteria are not the same, and calling the conditions they describe by the same name would be misleading. If and when we refer to disease names, we will refer to Oxford as describing idiopathic chronic fatigue; Ramsay as ME; Fukuda as CFS; CCC as ME/CFS; ICC as ME; and NAM/IOM as ME/CFS (though SEID was suggested, it was not adopted). With the exception of Oxford, this is how each diagnostic criteria describes the disease it defines. Footnote: In agreement with CCC: “If the patient has unexplained prolonged fatigue (6 months or more) but has insufficient symptoms to meet the criteria for ME/CFS, classify it as idiopathic chronic fatigue.” This describes Oxford. ”

With something that didn’t attribute names to the various diagnostic criterion. By doing this, the article seems to have made some very definite statements about what diagnostic criterion diagnose what, as well as somewhat questionable distinctions between terms that at least on the diagnostic criterion refer to as a synonym. Not surprisingly, these things mean that, at least for me, there wasn’t an awful lot of demystifying going on.

* Although given ME Action’s homepage refers to ME and CFS, but not ME/CFS, does it represent people wth ME and CFS but not ME/CFS? This isn’t a serious question – but rather noting the potential confusion for people that the labels used here could lead to.

Thanks for that — genuinely, I appreciate constructive criticism, and it helps that I agree with you! I hovered over deleting that paragraph a few times.

It’s #MEAction’s stance to refer to the disease as ME. However, if we were talking about a study that uses Fukuda, calling it “ME” is disingenuous. That’s a criteria for CFS. I wanted to set this out in the beginning so that people understood if I did not use the name ME, why I wasn’t doing so.

Then the whole article I only ended up referencing criteria names for the most part, and not disease names at all! So that was kind of for naught.

You’re right that I’m not trying to lead the audience to the ‘right’ conclusion. I honestly want people to stare at the criteria and get to know each of them, talk online, ask questions and do some further investigation on their own, and come to their own decision. There is so much frustration around the criteria that I’m hopeful that there are those who will find a neutral presentation of the information a breath of fresh air.

Thanks, I will consider removing that paragraph! I think you’re probably right that it could be confusing.

It was definitely intended as constructive 🙂 I wouldn’t say the whole paragraph needs to go – just the bit where it starts talking about ME, ME/CFS and CFS as different illnesses, and infers semantically that only Ramsay and ICC cover ME.

How about something like the below? Note – if useful, just take the bits you like, and leave the bits you don’t.

“Generally speaking, when referring to the disease, #MEAction uses ME; however, these diagnostic criteria are not the same, and while some people with the same illness could and would be captured by different criteria, some of these criteria are so broad (in particular Oxford and Fukuda) as to capture people who many would not consider to have ME. The other criteria, while clearly aimed at what we understand as ME, have some differences that may include or exclude different people depending on their symptoms. At this stage, researchers have used a range of criteria when recruiting for studies (sometimes using more than one in a piece of research), and doctors have used different criteria when diagnosing, making an understanding of what various pieces of research mean, and what a diagnosis of ME (or ME/CFS, in jurisdictions that use this term for the illness) means, confusing.”

I would definitely leave out “With the exception of Oxford, this is how each diagnostic criteria describes the disease it defines.” – not least as the ICC explicitly notes it is referring to CFS, but is deliberately changing the term it uses to refer to this – so using the ICC text to suggest it does not refer to CFS is logically and semantically incorrect.

It sounds like ME Action supports the ME criteria, either Ramsey or the ICC. Is this correct?

Hello, Pam! This article is part of the Policy and Values process, which will end with soliciting the opinions of the community to determine what criteria or criterias #MEAction will support. This article will hopefully inform people regarding the different criteria — how they are the same and different — allow them to think about clinical versus research — and arrive at an informed decision. Too much of what’s online is simply repeating talking points, some of which are either incorrect or misleading. The diagnosis is more than a political hot button. It’s directly related to whether people will or will not receive compassionate, timely care. I hope we keep that in mind as we move forward!

Excellent and helpful article. I just wish that you would use the word “criteria” correctly. It is a plural noun, not a singular. The singular form is criterion.

For example, it would be correct to say that the Oxford criterion is severe, disabling fatigue of new origin present at least 50% of the time.

It is also correct to say that the Post-infectious Oxford criteria are:

1. Severe, disabling fatigue of new origin present at least 50% of the time

2. Onset proved to be during or post-infection

To my mind this misuse of terms makes a thoroughly researched article seem poorly done. Which it is not.

On the positive side, I love the comparison chart, despite the grammatical imperfection. It succinctly summarizes the current state of diagnosis. Nice work.

You’re the second person to mention that! And it bugs me as well. It did the entire time I wrote the article.

However, the reason I stuck with it is that the criteria are called “the Canadian Consensus Criteria” — even though that describes one criterion, as a whole. Moreover, we always say “the diagnostic criteria” when referencing a single list of symptoms to diagnose someone, not “the diagnostic criterion”. If you can shed light on this, I’d appreciate it!

I think the CCC refer to a set of criteria, not just one criterion.

There’s a typo in the section on Ramsey – under cognitive symptoms it should read ‘anomic dysphasia’ not ‘…dysphasia’ which is swallowing difficulties.

Thanks, Kate! I’m making a few fixes tomorrow and I’ll check that out.

I agree it is very important that the community has good information to look to for understanding the different criteria.

There are some inconsistencies in this that would be good to correct. One of those is under the “Time to Diagnose” you have ICC is three months.

Here is the actual quote from the ICC ““The Canadian Consensus Criteria were used as a starting point, but significant changes were made. The 6‐month waiting period before diagnosis is no longer required. No other disease criteria require that diagnoses be withheld until after the patient has suffered with the affliction for 6 months.”

For anyone trying to wade through how to use the ICC diagnostic criteria I recommend the ICC Questionnaire from http://www.MEadvocacy.org (resources page).

English – https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/meadvocacy/pages/22/attachments/original/1478717636/ICC_Questionnaire_Nov_2016.pdf?1478717636

Spanish – https://assets.nationbuilder.com/meadvocacy/pages/2292/attachments/original/1552023295/LOS_CRITERIOS_ICC_QU%C3%89_SON__Y_COMO_ENCAJO_EN_LOS_CRITERIOS.pdf?1552023295

Dutch – https://assets.nationbuilder.com/meadvocacy/pages/2292/attachments/original/1552413206/ICC_Questionnaire_Dutch_2019_March.pdf?1552413206

Colleen, you’re absolutely right! I’m tweaking a few things tomorrow morning and I’ll change that with a note.

Thank you. I caught several other inconsistencies, would you like me to send you those or wait until you repost?

Feel free to email that to me if you’d like Colleen!

I am way below baseline right now, so it isn’t organized..

To start though, please review the ICC information on the chart. A correction in the required symptoms section is needed.

Also under the ICC section the paper states: “It has one, required symptom”. That is inaccurate. To see that the ICC has several required symptoms go to the easy to read ICC Questionnaire:

https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/meadvocacy/pages/22/attachments/original/1478717636/ICC_Questionnaire_Nov_2016.pdf?1478717636

Maybe reword to: *Required symptoms:* *Post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion * *is one of several required symptoms.*

I will wait until the updates are posted and review that as I am able.

I am working on an email, in the meantime please review the ICC information on the chart. A correction in the required symptoms section is needed.

Also under the ICC section the paper states: “It has one, required symptom”. That is inaccurate. To see that the ICC has several required symptoms go to the easy to read ICC Questionnaire:

https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/meadvocacy/pages/22/attachments/original/1478717636/ICC_Questionnaire_Nov_2016.pdf?1478717636

Suggestion reword –

Required symptoms:

Post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion is one of several required symptoms.

I am going through the updated version. I would like to see this section reinstated with the noted correction:

“however, these diagnostic criteria are not the same, and calling the conditions they describe by the same name would be misleading. If and when we refer to disease names, we will refer to Oxford as describing idiopathic chronic fatigue; Ramsay as ME; Fukuda as CFS; CCC as ME/CFS; ICC as ME; and NAM/IOM as ME/CFS (though SEID was suggested, it was not adopted).”

Correction – NAM/IOM would be best for clarity to not have the same label as CCC. An alternative being used is ME/CFS-SEID. The community is confused enough without having CCC and NAM/IOM using the same exact label.

(NOTE: I tried to send a reply using the email but it didn’t post – if it posts it can be deleted.)

Hi Colleen,

Take care at that end – just commenting on that paragraph you were asking to be reinstated – that paragraph is inconsistent with the text of the ICC, and somewhat arbitrarily assigns illness names in a way that is neither logical (ME/CFS as a distinct illness to CFS as a distinct illness to ME, when the ICC criteria plainly state they’re using ME as a synonym for CFS, in the hope of replacing it as a term). I was the one that suggested its removal, as it is far from clear that the statements in this paragraph were correct, made sense, or would be helpful to readers.

For more info, see my earlier comments in reply to this article.

Spect scans like what Hyde is using are commonly used in brain injury circles. There was a VP1 blood test in the 80s by Mowbray which Spurr and Richardson was using so there was a biomarker which existed. Mowbray also had a more sensitive Epstein Barr test. Its all been forgotten just like people with ME and CFS.

Note that the article says that there is no test *specific* to ME and ME alone.

An EBV test tests for that single virus which lots of people carry, even if they don’t have ME. VP1 is for enterovirus, right? You can have an enteroviral infection and not contract ME.

What we have is a lot of tests that show something is ‘off’ — but so far, none that are unique to ME alone.

i got ME when i was 21, im 60 soon. I never got a clear diognosis over all those yrs. so i quit going to doctors. They told me i was depressed and tried sending me to a shrink…no thanks. Im not mentally ill, ….never was. I recall the day i got sick in a motel room handling dead mice out of traps.

to date., i dont understand why every country has a different outline of symptoms etc. to properly diognose this illness but then im not the smartest tool in the shed either.

The lack of one, single diagnostic biomarker is, I think why there isn’t just one criteria, Reginald.

I had an interesting experience once regarding a prescription a non-US doctor had given me. It was a higher dose of injected B12 than I guess they give in the US. I mentioned that it’s perfectly safe to the US pharmacist: not only do they give at higher doses in other countries, in some countries it’s sold over the counter at that dose. The pharmacist’s response? “Well, but that’s over *there*.”

People will argue that their way is best ’til they’re blue in the face.

Perhaps that’s why we’ve struggled to get one criteria to be accepted everywhere.

I really don’t know how you all can get your heads around all this information, but am grateful it is

published. Have had CFS/ME for 21 years, with a lot of head symptoms. I get treated by a physio

who has had it, and recovered, but only ever had the flu like symptoms. However, my question to

anyone out there, is do you get incredibly high B12 blood serum readings. This began happening to me

a couple of years ago. My gen prac was injecting me on a regular basis. He now refuses to, and says not to worry about it. I don’t appear to have any severe problems with kidney or liver function, which are

the only reasons given, I know that many CFS/ME folks have this problem in blood test results. There

must be a reason. I am chronically ill, and getting weaker these days. I thank Jaimee for your contribution, and can’t understand why everyone has to criticise correct English if the meaning is easily understood.

Regarding B12, I personally haven’t had high readings, even though I take a lot. I haven’t heard much about this from others, either; sorry Billie!

Jaime, in the beginning you describe at some length a multi-symptom version of Oxford, as though it were a player of consequence in the diagnostic and criteria arena. You follow up with a much more brief account of the one-symptom version, noting its use by the biopsychosocial school.

Yet at the end of the report you pay all respects to Oxford as a single-symptom entity, not bothering about the multi-symptom version.

I applaud your latter description, focusing on the one-symptom version, because that is the version that is important for history, for science, and for the history of science.

However, the mismatch between beginning and ending descriptions could use a little balancing. May I suggest offering more on the tremendous impact of the one-symptom version at the top of this paper, perhaps noting the harm to research and patient care? You could then rightly limit discussion of the multi-system version to the fact of its existence and far lesser impact.

Either top or bottom you probably ought to report the very consequent fact of Oxford’s official rejection by US federal agencies following a report by federally-appointed group condemning it as non-specific and useless. That was a few years back — certainly not soon enough!

If inclined, you could note the key role of definitions, criteria, etc as shown by the dreadful and enduring harm done by the non-descriptive one-symptom Oxford — as it enabled Peter D. White and associates to assemble cohorts of vaguely fatigued people (47% co-morbid for depression in PACE) in order to claim effectiveness for CBT and GET, thereby re-casting a terribly disabling neuroimmune disease into a matter of “false beliefs.”

And for that its use has been officially rejected by the US federal agencies

Thanks Jaime for your perseverance, it remains a mystery, I even asked Dr. William Walsh in the USA, the founder I think of treatment for the Methylation Cycle in the brain, which I think has kept me going for many years, expensive as it is.

Thank you for this helpful article. Please make a correction and use the word “criteria” correctly as a plural noun.

I’m looking forward to your survey of expert ME researchers and ME clinicians addressing the same questions.

The proliferation and confusion of criteria for ME is a huge obstacle in diagnosing/researching this illness, and, while well-meaning, this guide is lacking clarity re. Oxford and Ramsay.

PIFS, a post-infectious syndrome, was a *subtype* of Oxford CFS. And in reality it was fast forgotten. CFS without infectious trigger was far too easily – and catastrophically – conflated with ME.

In your description of Ramsay, ‘peri-onset’ is mentioned. I have no idea what peri-onset means, have never come across it and it is not written on page 29 of his book, which refers simply to onset.

And Ramsay spoke crucially of feeling awful and of fatigability on trivial exertion, PEM had not yet been coined. So how can ‘Ramsay *mention* post-exertional malaise (though he doesn’t label it as such) in his description of peri-onset symptoms’ if PEM did not exist as label when he wrote his book? Am sorry but this along with ‘peri-onset’ lacks clarity.

And the misconceptions and clarifications are a little garbled, to be honest.

I know about Ramsay as the late consultant neurologist Peter Behan who diagnosed me worked with Ramsay and wrote preface to his 1986 book. And I witnessed the hijacking and disappearing of ME via Sharpe’s Oxford Criteria in 1990s.

The proliferation and confusion of criteria for ME is a huge obstacle diagnosing/researching this illness, and, while well-meaning, this guide is lacking clarity re. Oxford and Ramsay.

PIFS, a post-infectious syndrome, was a *subtype* of Oxford CFS. And in reality it was fast forgotten. CFS without infectious trigger was far too easily – and catastrophically – conflated with ME.

In your description of Ramsay, ‘peri-onset’ is mentioned. I have no idea what peri-onset means, have never come across it and it is not written on page 29 of his book, which refers simply to onset.

And Ramsay spoke crucially of feeling awful and of fatigability on trivial exertion, PEM had not yet been coined. So how can ‘Ramsay *mention* post-exertional malaise (though he doesn’t label it as such) in his description of peri-onset symptoms’ if PEM did not exist when he wrote his book? Am sorry but this along with ‘peri-onset’ lacks clarity.

And the misconceptions and clarifications are a little garbled, to be honest.

I know about Ramsay as the late consultant neurologist Peter Behan who diagnosed me worked with Ramsay and wrote preface to his 1986 book. And I witnessed the hijacking and disappearing of ME via Sharpe’s Oxford Criteria in 1990s.

Great work on the changes Jaime – think they make the document more robust and targeted. As said before, it’s an excellent overview of the various diagnostic criteria. Also dropped a few paragraphs with criteria into Grammarly and it didn’t have an issue with all bar one, where it definitely should have been criteria in any event (Grammarly is good, but there’s no such thing as a grammar program made for all situtations).

How do some of you manage such lengthy and detailed responses that I, for one, am unable to read or ingest?

I am sure there is useful information here but it makes my head spin trying to read it.

I have a medical background but have been ill since 1992 so following the chart was easier for me.

Thank you.

For me at least, it’s probably a combination of familiarity with the subject material (it’s easier to process things that I’ve already had some exposure to, even if I’ve forgotten most of the details), and prioritising that response (my ‘big’ initial response was literally my second-largest activity for the day it was made, and I had PEM from writing it the day after – silly me!) It was very challenging to write, and I had to go back and re-read bits repeatedly, due to memory issues. Took me a long time as well. I’m also very lucky to only be ‘mostly housebound’ (so on the gentler side of moderate ME).

You shouldn’t feel bad at all if it was difficult to get your head around, particularly if you haven’t looked at these criteria in depth before but even if you have – one of ME’s quirks (well highlighted in the illness criteria, that have some key ‘core’ symptoms, like PEM, and then a laundry list of supporting symptoms that vary by patient) can affect different people quite differently.

Hi. I am in Australia, living with ME/CFS for 15 years. I have seen 4 specialists and have never had my disability referred to as ME. It has always been either CFS or more recently ME/CFS. I was diagnosed using the CCC and my specialist and the one who came here from Belgium were both of the opinion that ME, ME/CFS and CFS were the same condition. My specialist helped to develop the ICG. Recently Emerge, our support and advocacy organisation, has encouraged us as a community to refer to our illness as ME, due to the negative association that “chronic fatigue” has in the disability support sector. They encourage our medical professionals to do likewise. But we have never considered these all to be different conditions here, as I gather (from reading a lot of comments) seems to be the case in the US? Could you explain this? Thanks

Hi Janette,

Each criteria has attempted to act as a diagnostic tool to capture the true nature of the disease, which have been called ME, ME/CFS or CFS, with different criteria using different terms. In that sense, the name is attached to the criteria. (Although, in the case of the NAM/IOM criteria, the recommendation that the disease be called “SEID” was never accepted nor implemented by the clinical or research community.)

Because each set of criteria has different requirements, the patient cohort it “captures” will differ. Fukuda would capture far more people than CCC, for example. Fukuda captures more people (in part) because it has fewer symptoms that are absolutely required, and everything else is a grab bag. To say that this makes Fukuda CFS a “completely different” disease than CCC, however, is not QUITE right. How could it possibly be, when half of people who meet Fukuda also meet CCC?

What we’ve ended up with is a lot more complicated, with disease-definitions that (mostly) have a significant degree of overlap: if you meet CCC, you certainly also meet Fukuda, but it doesn’t hold firm the other way around. Researchers and clinicians would say that this does not mean that “Fukuda CFS” is a different condition from “CCC ME/CFS”, but different attempts at defining the same basic disease entity, with relatively more or relatively less success. We can’t say with more or less accuracy, since there’s no concrete way to determine that right now. Not without a blood test that identifies those with the disease.

It’s very confusing and tangled, but my impression is that we’re working our way towards clarity. Hopefully we’ll discover a blood test or biomarker that truly differentiates pwME from others, and this diagnostic tangle will resolve. Until then, there will continue to be a lot of debate on the matter.

Hi Janette,

I’m in Australia and I was diagnosed with ME. My GP wrongly interpreted this as being the same as CFS and that’s when I was given harmful treatments that took me from moderate to severe ME.

In Australia, the government and medical community’s definition of chronic fatigue syndrome (2002) is very different to the CCC/ICC.

This article has a chart which outlines the differences between Australian CFS and ICC ME (sorry I can’t paste the chart here):

https://meaustralia.net/2019/07/01/failure-to-update-medical-guidelines-see-people-with-me-denied-disability-support/

The Australian guidelines have led to mistreatment and misdiagnosis: Griffith Uni found that of 535 Australians diagnosed with CFS by a GP, 24% had they symptoms explained by another disease or illness (ever had someone say to you “oh, I had that but it was actually xxx” so they don’t ‘believe’ in CFS?!). Only one third of people met the ICC ME criteria.

More here: https://meaustralia.net/2016/05/26/australia-2-in-5-cfsme-diagnoses-wrong/

The ICC states:

“Name: Myalgic encephalomyelitis, a name that originated in the 1950s, is the most accurate and appropriate name because it reflects the underlying multi-system pathophysiology of the disease. Our panel strongly recommends that only the name ‘myalgic encephalomyelitis’ be used to identify patients meeting the ICC because a distinctive disease entity should have one name. Patients diagnosed using broader or other criteria for CFS or its hybrids (Oxford, Reeves, London, Fukuda, CCC, etc.) should be reassessed with the ICC. Those who fulfill the criteria have ME; those who do not would remain in the more encompassing CFS classification.”

Here’s a fact sheet that ME Australia took to the meetings with the Health Minister and others: https://meaustralia.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/meaustralia-fact-sheet.pdf

Thanks so much for tackling this complex, confusing and frustrating area of ME in this article. And thank you for your open and considered responses. It’s wonderful to see how you and #MEAction practice democracy in action, even in something as complicated as reviewing an article on the multitude of ME diagnostic criteria. It makes for a stronger and better piece and makes for a more empowered community.

Thank you for tackling this head on. It’s brave but needed!

I think a big aspect of misunderstanding is between how you need a criteria to work in clinical, research and support group settings. There are slightly different needs. A research study might want to be more specific without this being arbitrary (not like the eye colour example). In that setting it is better to exclude people if in doubt to avoid unnecessary noise.

That doesn’t work so well in a clinical setting because patients might benefit from similar advice and treatment even though they don’t meet a narrow criteria. For example, early advice on Pacing is probably a good idea for this group too, rather than sending them away without a diagnosis or direction.

Also rejecting them from our community as not meeting True ME status seems to be a misuse of diagnostic criteria. Because of the PACE farce I think pwme can be overly suspicious of the people themselves who do not meet strict criteria, but this isn’t the problem. They’re just sick and struggling too even if they don’t meet all of ICC. Very frustrating for them to not be accepted or treated. If ME is the closest diagnosis to what they experience they should be able to find support without judgment in our community.

My personal opinion is we could do with agreeing a strict ME criteria for comparable research (and also subgroups within that) and then having an Atypical ME broader clinical diagnosis for people who don’t fit in neatly (and these people also get more thorough differential diagnosis testing). For example, this type of approach is used for people on the Autistic Spectrum who don’t fit neatly into the criteria.

The new NICE guidelines are likely to introduce yet another criteria next year, hopefully improved, though of course it will be from the clinical management perspective rather than with research purposes in mind.

Jannette comments that she has never had anybody in Australia just call the illness M.E my experience is different Prof Denis Wakefield in 1992 diagnosed me with Post Viral ,M.E and then 7 years ago Prof Pete Smith just called it M.E he is the consultant for the NCNED research centre

This explains why GPs find it so difficult to understand ME! A month ago a GP who I have seen for around 20 years said he didn’t understand ME and it kept changing. He is quite right, and I admire him for saying so. So many criteria, so many differing opinions. Probably so many conditions! ( see the researcher who thought there are many elephants in the room!) it will really help if there is a blood test, or if each area ( thyroid, infectious etc) do the correct tests in their area. I have a T3 Conversion problem. Someone else may have Lymes etc etc etc. At present ME is a sink diagnosis and a dead end.

This is an awesome article and must’ve been a huge amount of work. Thank you so much, Jaime

I agree completely. Perhaps an editor is needed: someone with a science/english background who could put your article into a more coherent form. most of us can’t comprehend all the various definitions and the (frankly) confusing conclusions. we really do want to understand, but, basically, it’s impossible….and most of us, while being very ill, are well educated. each of us ‘knows’ what’s wrong with us, but the write-ups often shed little light on how we might all have the same disorder. thanks loads and keep up the good work. it is much appreciated.

The IOM/NAM criteria have biomarker, reduction in VO2 Max with PEMS. At my level of understanding this is consistent with the inclusion of breathing symptoms in both consensus criteria.

I have sleep apnea and live at 9500’ with mild related hypoxia. I watch my oxygen saturation closely. Anecdotally it definitely worsens with an increase in ME symptoms.

I call these flares and the overlap with MS flaring is also important. I’ll throw out a general comparison – ME is MS as IBS is to IBD.

Hi, thank you for this article. I have awful brain fog so it’s hard to write. I’m confused about diagnosis because I have long standing MDD and anxiety disorders (sometimes thought to be Bipolar 2).

My fatigue had a sudden onset after doing two low impact exercise classes about 9 years ago. I never recovered. I meet the CCC and NAM criteria with flying colours but I think most ME/CFS criteria exclude people with psychiatric diagnoses.? I’m surprised that all these symptoms can be attributed to depression etc. eg Neuroendicrine, autonomic and immune symptoms.

I also have hEDS among other things.

I’d appreciate if anyone could steer me towards some information around this.

Thanks, Su.

Comments are closed.